C lean air. Spacious housing. Lush nature. Clear water. Quality roads. Fresh food. Social security. Safety. Speed. Comfort. Civil rights. Safe sanitation. Green Energy. 3D printing. Services grid. LED street lighting. Bicycles lanes. Silent zones. Smoker’s corner. Clean-tech. Close-circuit television. Shared work spaces. Permeable paving. Fossil fuel-free public transportation. Handicap accessibility. Women’s rights. Free movement. Open relationships. Internet of things. Gender equality. Equal opportunity. Public protest. Right to vote. Right to choice. Civil liberties. Same-sex marriage. Easy access. Childcare. Communal healthcare. Happiness. Idealism. Automated labor. Self-fulfillment. Altruism. Open society. Well-being. Organic farming. Opportunism. Humility. Cross-generational housing. Goodwill. Citizenship. Consumer culture. Status symbols. Spectacle. Media attention. Free WiFi. Wearable technologies. Health monitoring. Legalized downloading. Open source. Minimum existence. Sharing and caring. Private equity. Variety and repetition. Red Light Districts. Public education. Retirement benefits. Regulated divorce. Free spirituality. Subcultures. Trash collection. Surveillance. Building codes. Affordable living. Physical fitness. Life-styled communities.Compact cities. Eco-suburbs. Autonomy. Nudity. Sanitized coatings. Domestic rituals. Home ownership. Self-realization. Mutability. Storytelling. A day out. A culturally rich metropolitan life. The good life.

Whatever we conceptualize the good life to be, its pursuit -both as individual and collective endeavor- constantly drives societies and cultures. The good life, a concept originally rooted in Western thought, defines the desire towards happiness as Eudaemonia, which is achieved through self-realization, both by living and doing well. Coming from diverse contexts, and now citizens of nowhere and everywhere, we approach the good life as a collection of individual images that reflect our diverse cultural, political, social, and religious backgrounds. From Renaissance to Modernity, architects used to design projects as proposals of good life, be it a cabin in the woods or the jungle of contemporary city. Today, it seems an anachronism for a project to advocate for good life. A return to this ideal implies a necessity for architects to re-position their role within contemporary society and culture.

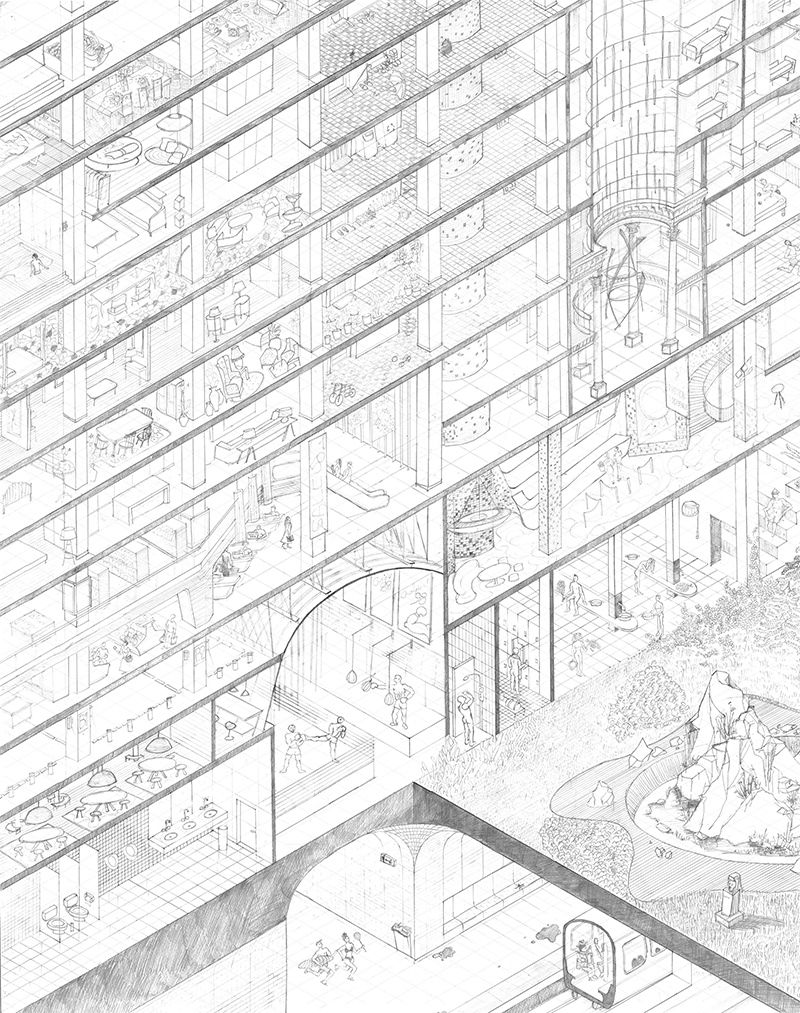

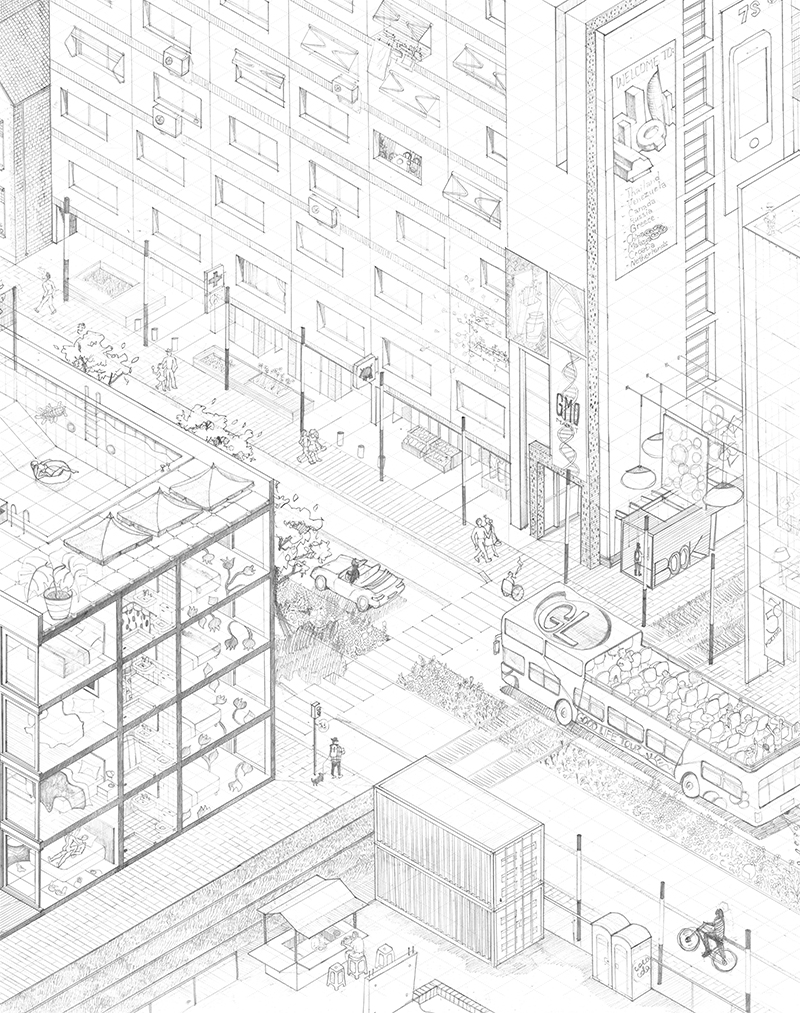

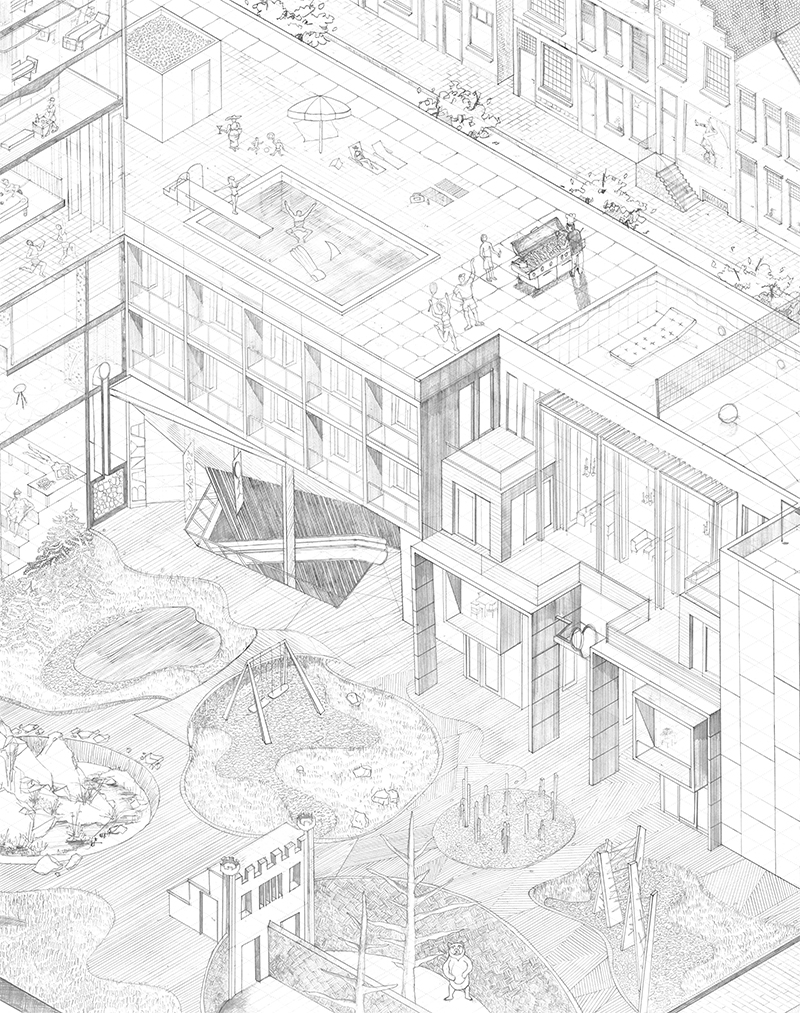

After endless posts and -isms that have attempted to frame the human condition in space we are brought in front of a—long-rejected—reality: a predominantly generic image of the city, the suburban, and the rural hinterland. Are we living in an achieved utopia that was once imagined by twentieth-century modern architects? Do standardization and prefabrication still promise the good life to the masses? Since the birth of modern aesthetics, architecture subscribes itself to the rhetoric of universality, of the universal man and his universal living unit and city…. It is through standardized representational methods and industrialized construction techniques that architects find efficient ways to create and recreate identical sites. From bleached tiled surfaces and chrome-coated furnishes to housing block layouts and Cartesian city plans, the aesthetics of anaesthetics are the most visibly generic prescription of universality, dictating architecture’s representational methods.

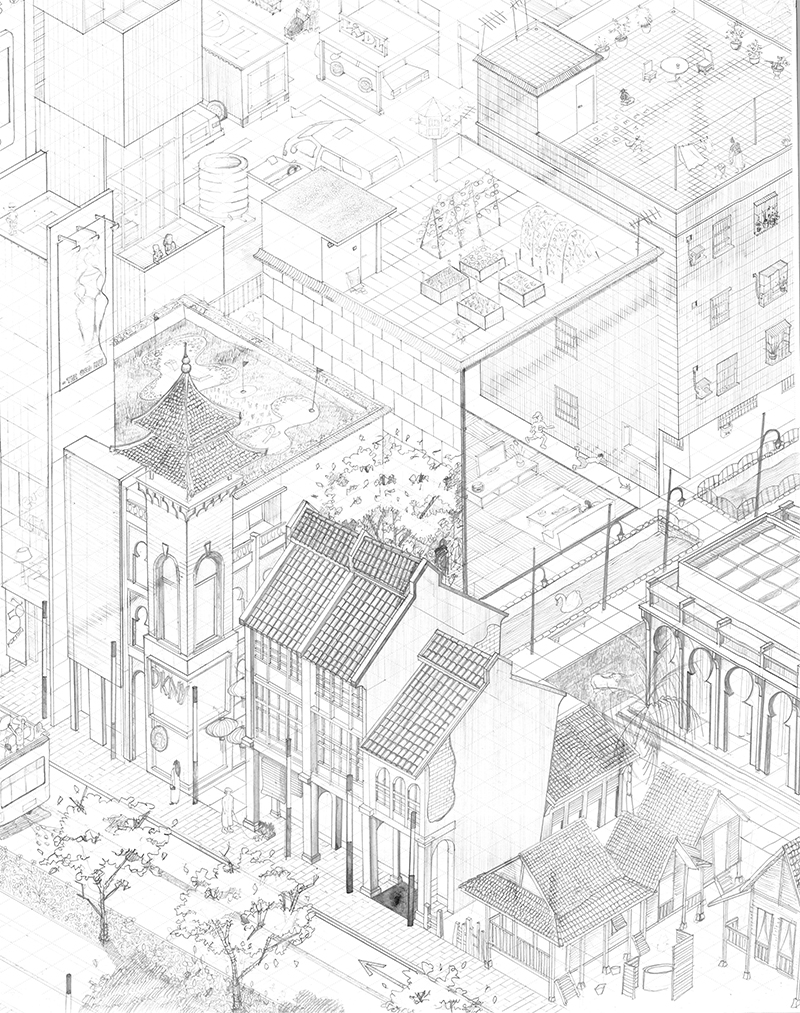

But have we standardized the rituals which once, but no longer, defined a good life? Rituals claim specific forms of architecture within the city at a variety of scales and for specific groups of people. On one hand, by acknowledging everyday rituals, the house -the most mundane architectural type- becomes a stage for performing daily acts. Within a generic spatial condition, the house defines the individual through its layout and architectural elements. On the other hand, places like public baths -singular architectural types and exceptional spaces of interior intimacy in the city- unveil the body, allowing us to overcome constructed hierarchical differentiation. Rituals have their own history to tell -one where the private and the collective good life is constantly mixed and transformed. By linking architectural types to cultural practices, one finds out that individual specificity, along with cultures and contexts, are not flattened despite the standardization and prefabrication of the architectural element, the housing block, and the landscape. Perhaps the good life only flourishes within seemingly generic environments – everyday for me, yet extraordinary for you.

By working within urban environments, we are always somehow complicit to other speculative agendas. These agendas, often bigger than us and perhaps out of our hands, formulate the city of today and tomorrow. But can complicity be a form of resistance, enabling architects to work the system from within? Each of our projects co-opts existing archetypes of representation as critical tools in order to position architecture as both a professional and intellectual act. After all, a jungle can grow from even the smallest seed. From humour to cynicism, from scenarios to resolutions, from analytics to polemics, a reality-based project can be both imaginative and socially pertinent, both professionally aligned and academically rigorous. The Good Life is one of awareness of the world around us and as architects we employ specific tools of representation to construct a depiction of this world. Such a depiction is as singular as the concept of the Good Life, but one which seeks to find unity among multiple Good Lives.